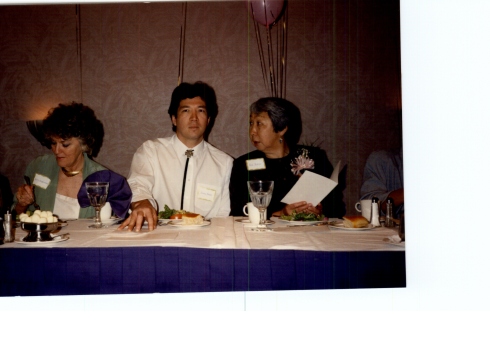

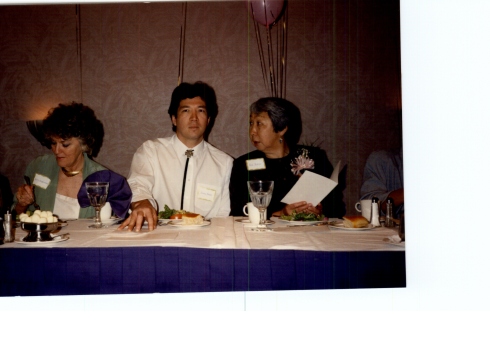

Mom’s retirement party; I read a poem. The Smallhouses drove down from Northern California, even Emmy was there, a hundred teachers, balloons, champagne, and a mariachi group. Where were you on that day? Elliot came all the way from Idaho from the Nez Perce reservation, in town on business. He came, hanging out with us. Where were you?

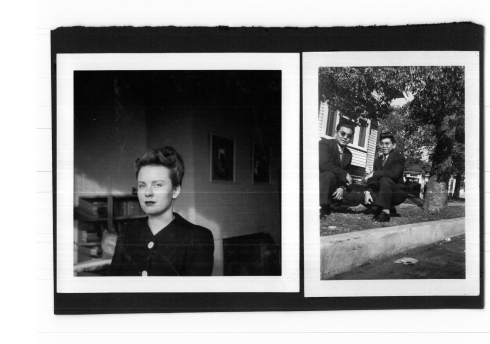

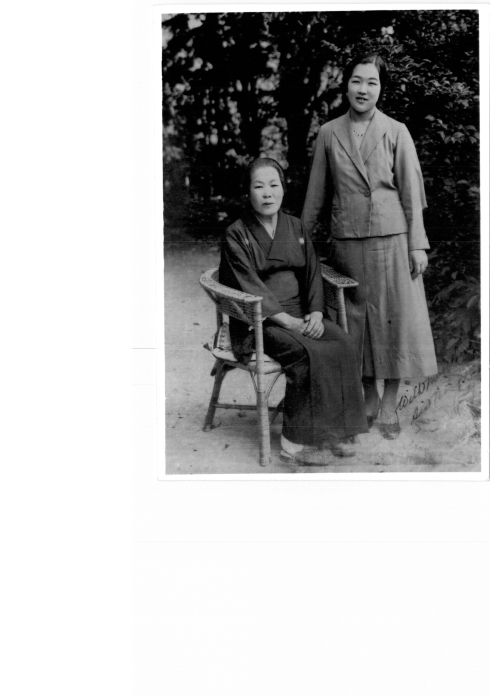

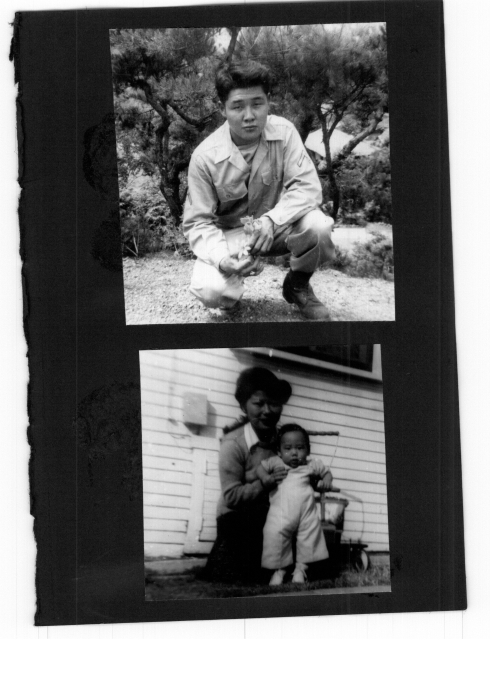

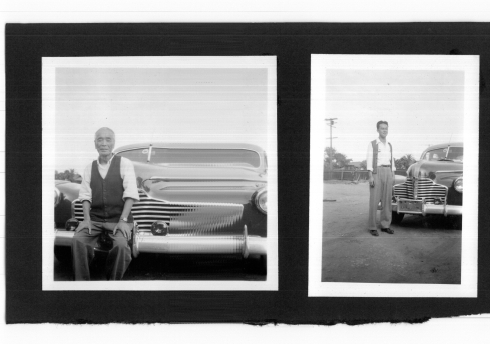

Our grandparents as newlyweds. Grandpa Otokichi looks a lot like Uncle Bill and Uncle Bob. According to records, born in 1877, attended school till grade 5 in Japan. Umeko Yamane, born in 1890, attended school till grade 8. Grandpa had been in California since 1899; Grandma had just arrived, 1913. It was arranged. They knew they didn’t know, hope the only little light they could hold forth. You wouldn’t recall anything about them. They never knew you either—though we met Grandma a few times in the facility in Santa Maria when she was ill. The Methodist Church rented them a room off the parking lot when they returned from camp. Grandma worked in the fields in strawberries and other crops and every day after work nursed her husband, laid out, ill from a stroke.

All those eyes—feel them look out of our eyes. Do you feel it? Were they watching you at rest, sitting on a downed tree on the trail, standing trees of the forest, alone, waiting for the the quiet. Waiting out the roaring that never ceased, even when the frequencies shifted beyond hearing. Smoking, certainly, maybe sucking a tall can in a paper sack, waiting to feel a little peace descending in bird song and tobacco smoke, occasional sounds from town.

Needless to say, there’s a thousand little snapshots of family gatherings where you never show up—you felt sorry for yourself, especially during the holidays, you felt an exile. “Who are those people? I don’t even know them anymore,” you said to me. After I sent you news about them, many letters, hundreds of postcards, told you how people were doing, what they were up to every time we met, that was the kind of bullshit you’d get back to me with.

It’s true, many of these people I didn’t know any better than you did. So what? That’s what the city is good for. You live with all these people; sometimes you see them, sometimes you don’t. You don’t know them all. You can’t. You may meet someone new on any given day. “I don’t like to be around people in groups,” you said. “I have social anxiety disorder.” You always had some excuse handy, even if you got it going around to a doctor’s office on the off-chance you might get a prescription.

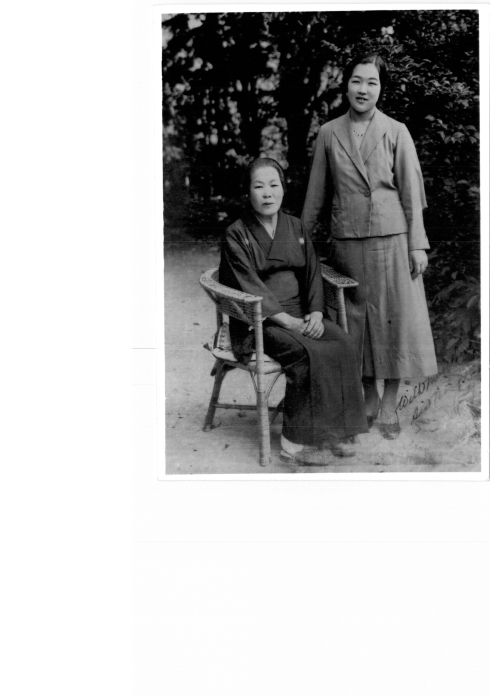

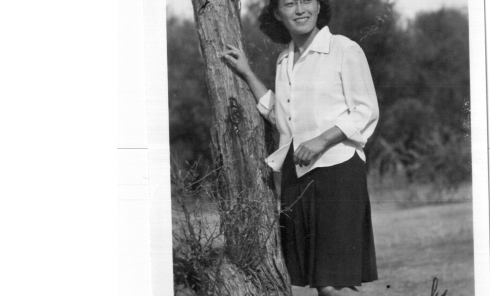

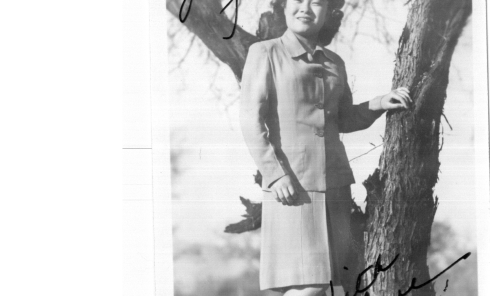

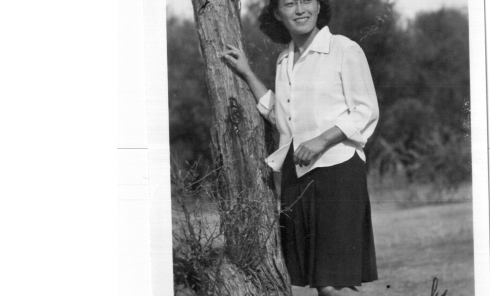

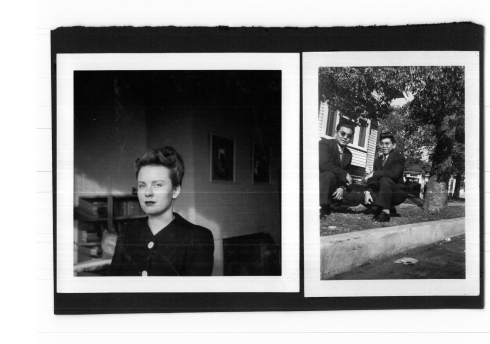

Our aunt, Mary Agawa, stands above her mother during their one trip to Japan. Mary returned from the trip ill with TB and died (in her mid-20s) shortly afterwards. Grandma lost her two eldest children to tuberculosis when they were young adults. By the time we met, her husband had died long before, and her health was broken.

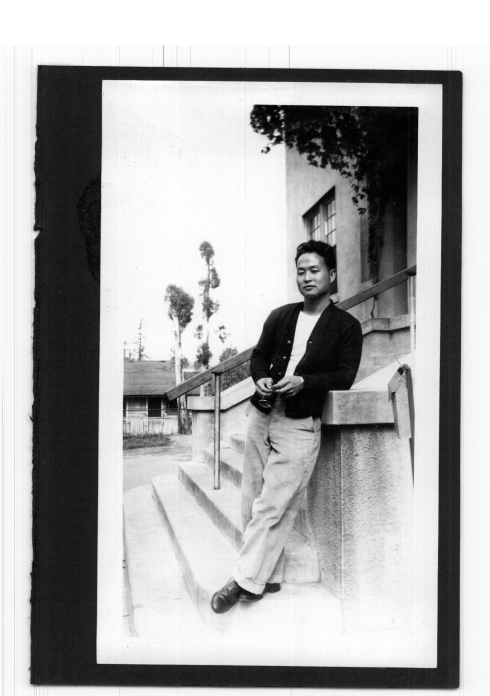

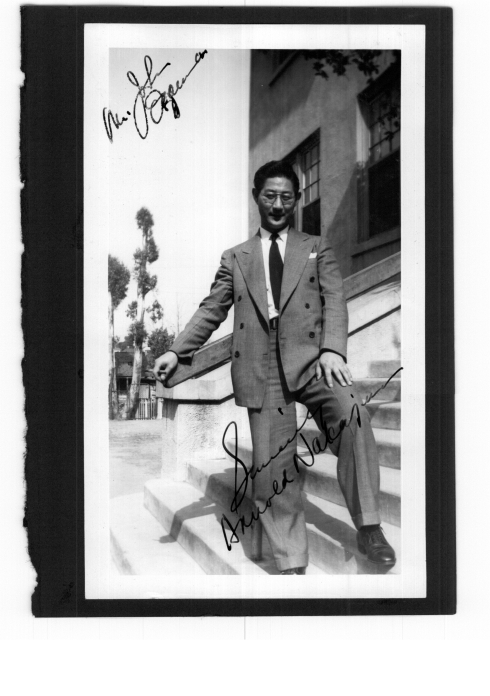

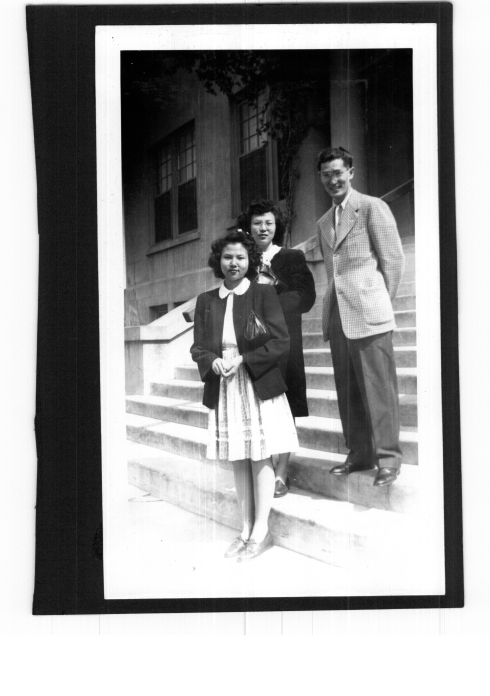

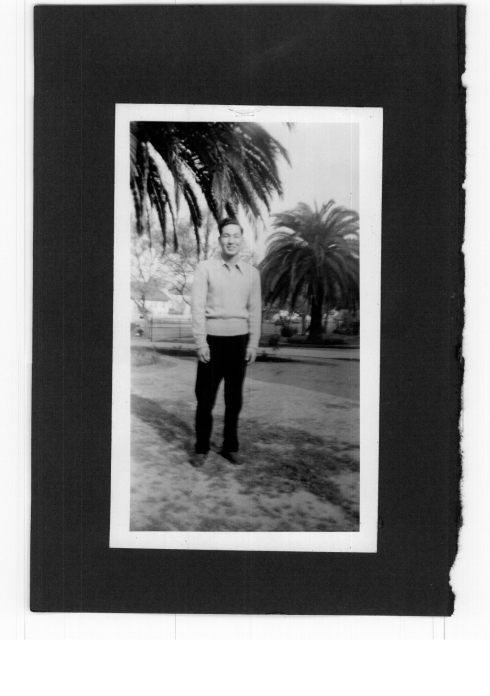

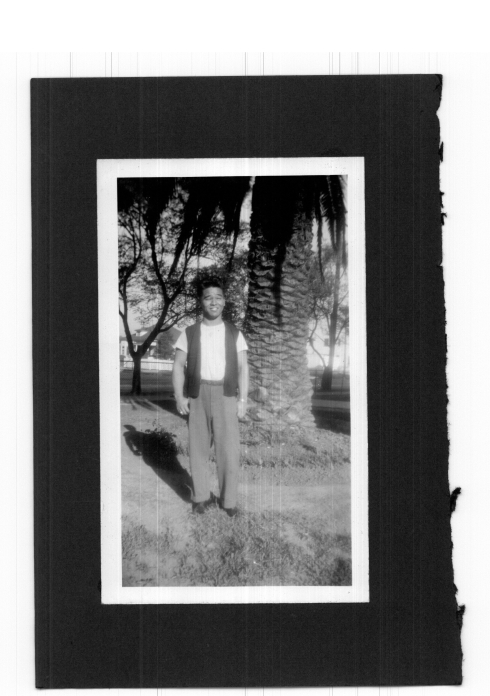

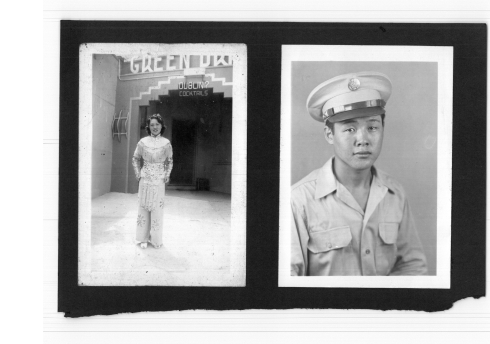

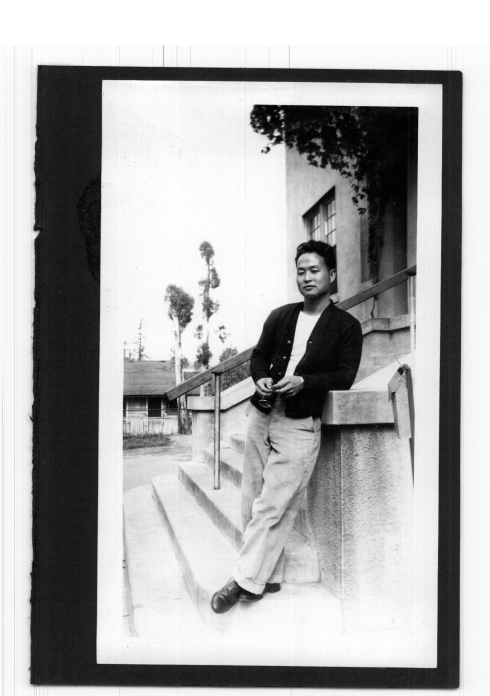

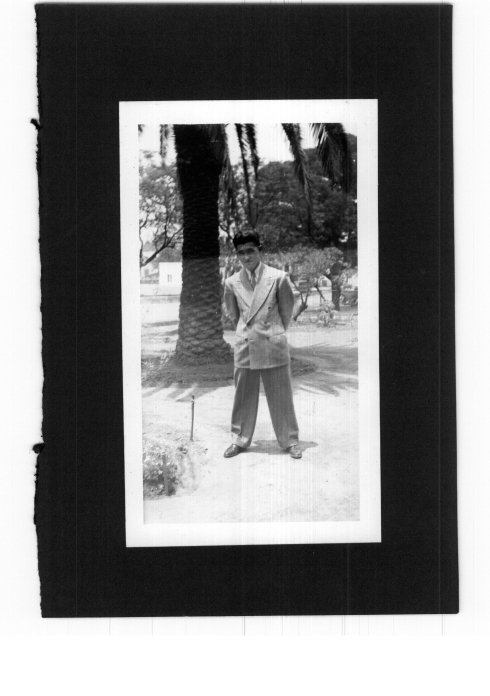

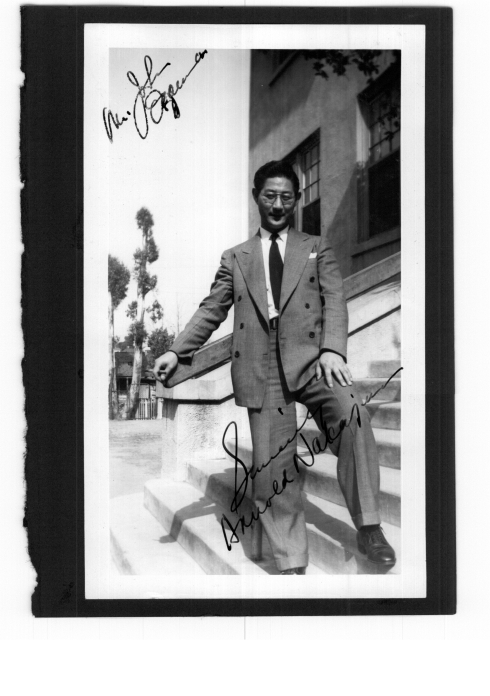

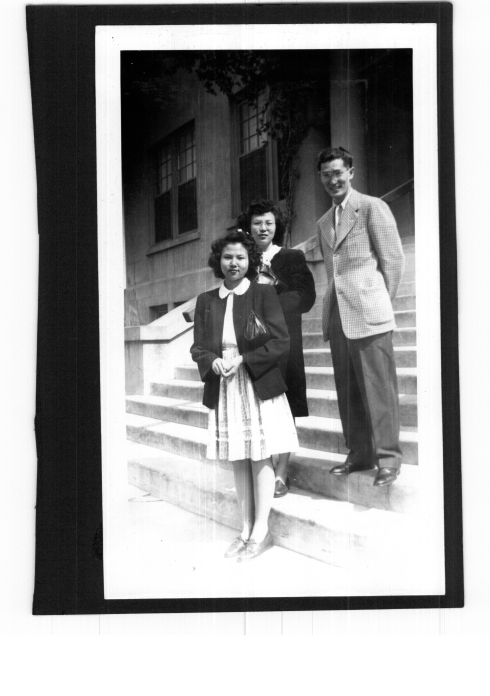

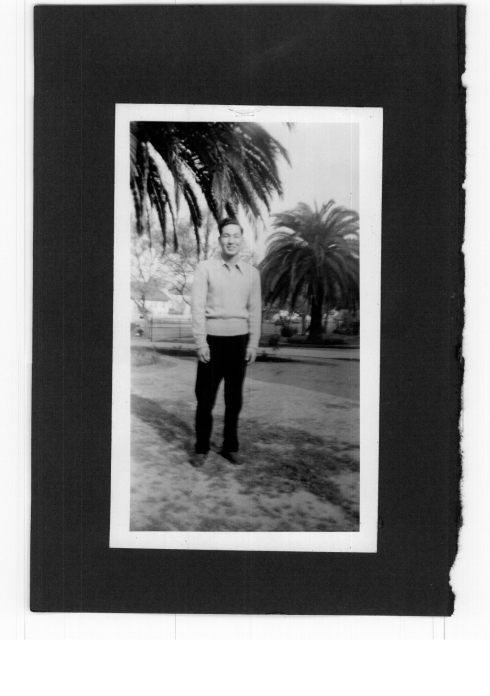

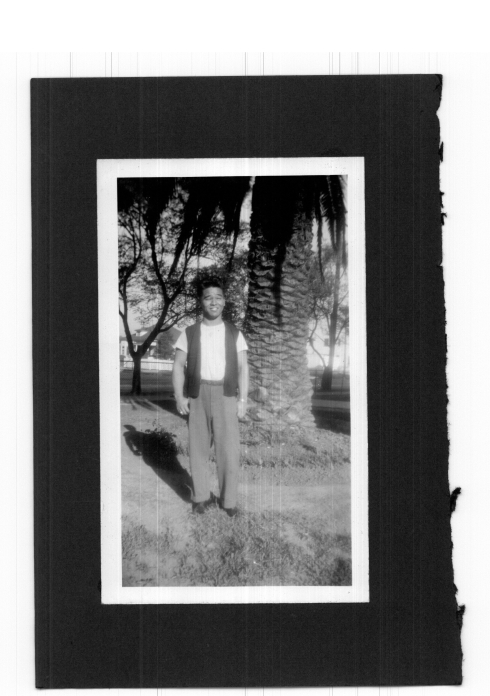

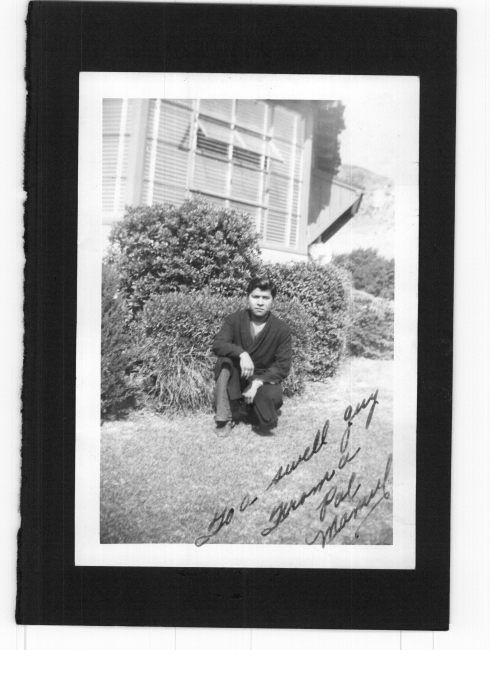

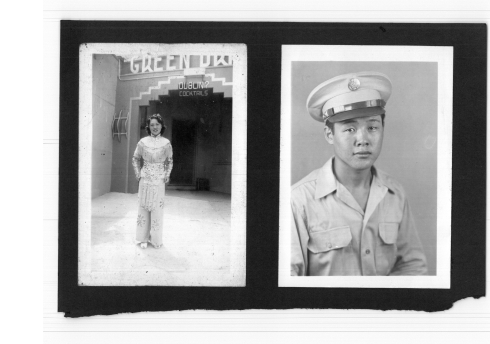

“Best of Everything— Terry Kubata”—all these pictures with these stairs or palm trees in the background were taken in Boyle Heights mid-1940s, where Aunti Fu and Uncle John met at the Fellowship Hostel on Evergreen Avenue, a block from Evergreen Cemetery. Terry Kubata would have been a resident like Aunti Fu and Uncle John, all these young Nisei released from the camps (I don’t know if Uncle John ever went to camp, because he spent the war isolated in tuberculosis sanatariums, the Barlow Hospital in Elysian Park, or one in the valley). Many of them just out of high school, just starting their lives, released from the camps. The war was over.

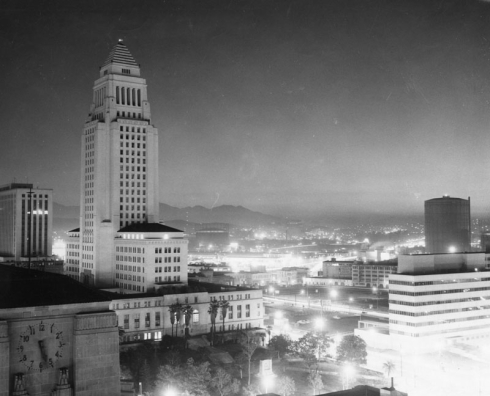

The Quakers (American Friends) and other churches took in internees released from the camps. Japanese Americans were given a bus ticket and $25 and told to go. In most cases the families had lost everything, their properties confiscated or sold for pennies on a day’s notice the week they left for internment, or they had their goods stolen from storage facilities like the Bekins warehouse on Fair Oaks Avenue in Pasadena. These young Nisei grew up in a California of racist Asian Exclusion Act laws, anti-miscegenation laws that prohibited people of color from marrying whites, their parents prohibited by law from owning land, racial real estate covenants were the law of land, made targets of violence and hatred and marginalized to “mixed-race” areas like Boyle Heights with its Catholic churches, Buddhist temples and Jewish shuls and centers. And then all of that was too complicated for you? What did it have to do with you?

The hostel is still at the corner of Evergreen and Folsom. It’s almost exactly the same, 70 years later, I’m not sure why. Here’s a snapshot looking toward Folsom. We walked around inside, the three story old-fashioned tenement building with an interior courtyard and the fountain long dry. Tiny, often windowless rooms open to long dim hallways with bathrooms at the end. At the bottom of the stairs in the basement, showers were provided in rough cement stalls with low concrete walls. A couple Mexicano caretakers live inside it nowadays, at least one of them with woman and kids. One was washing with a garden hose an old upholstered lounge chair in the parking lot at the rear of the building. Their music and TV can sometimes be heard coming out of the windows; maybe it was like that in the old days.

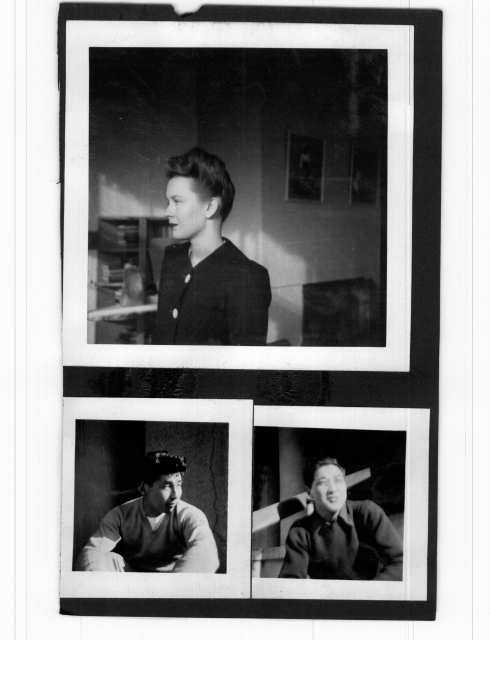

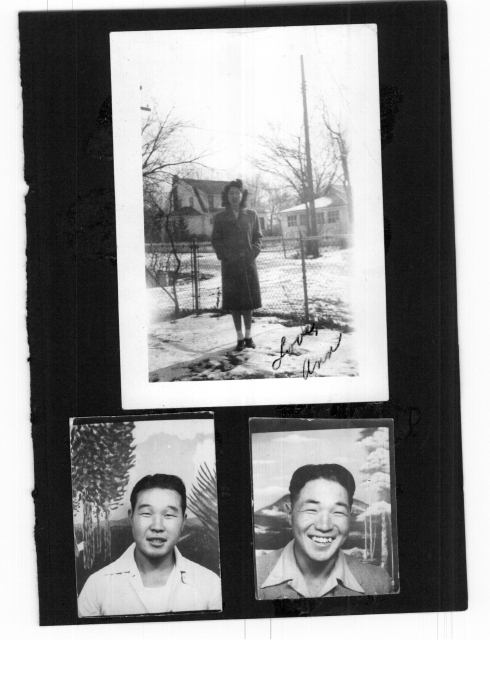

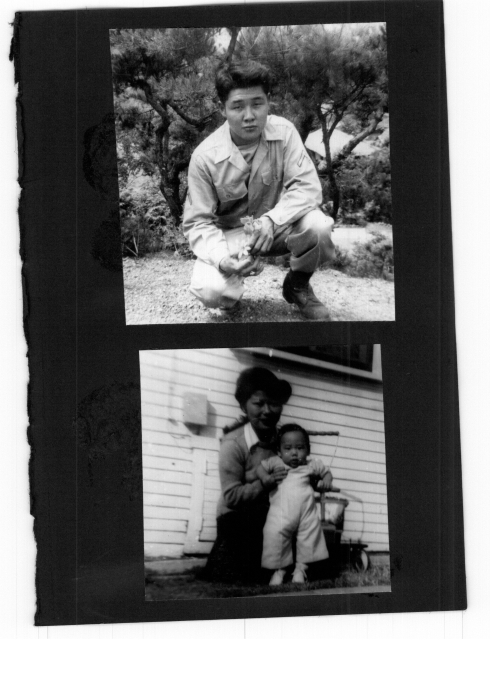

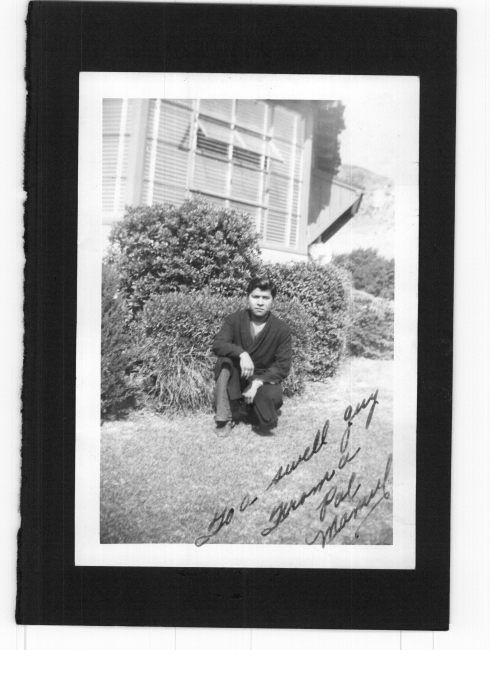

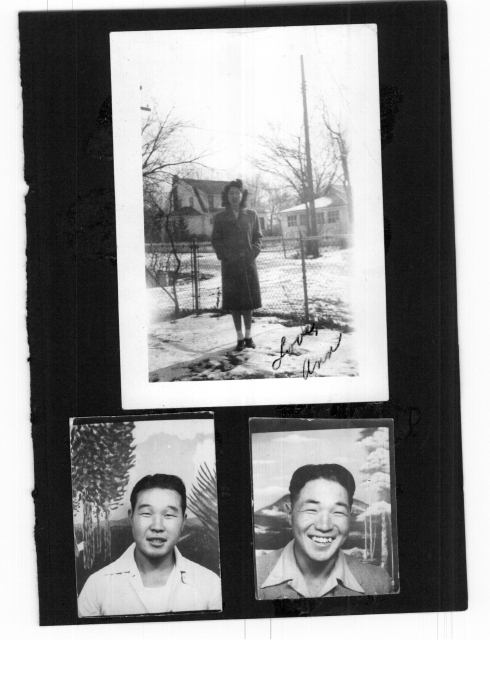

Here’s one of the guys who ran the place. “Arnold Nakajima”? He looks like my optometrist. The houses in the background are no longer there. The steps are exactly the same, the same sunshine, the people passed from the scene as if shadows. $35 a month, meals included, although I think the residents were required to help in the kitchen. Why not? This was a new era. They were no longer imprisoned. Uncle John, no longer confined to sanataria—his older siblings Tom and Mary had died from TB, while he had one lung left, the common treatment of the time to collapse one lung in the hopes the other “got stronger.” Seems to have worked for him and for Aunt Kay. It was a new era. They had new lives ahead.

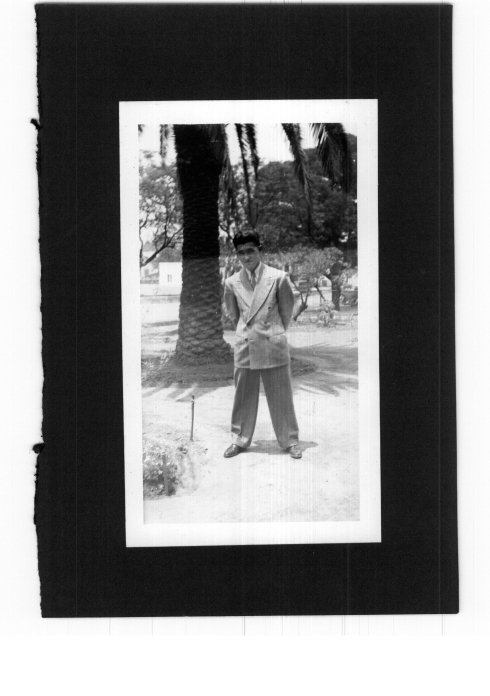

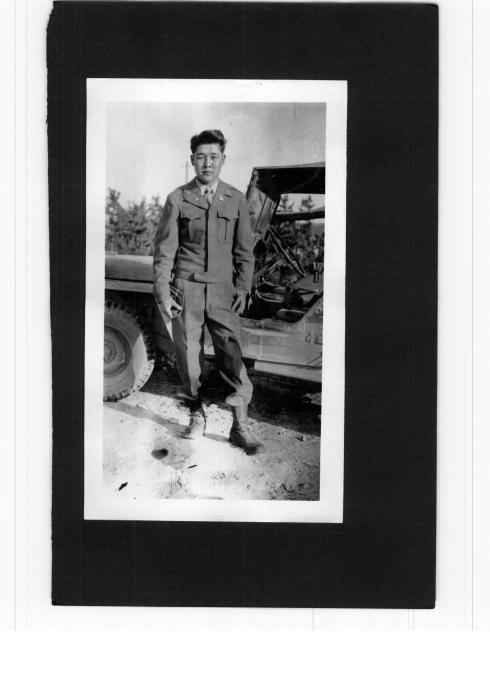

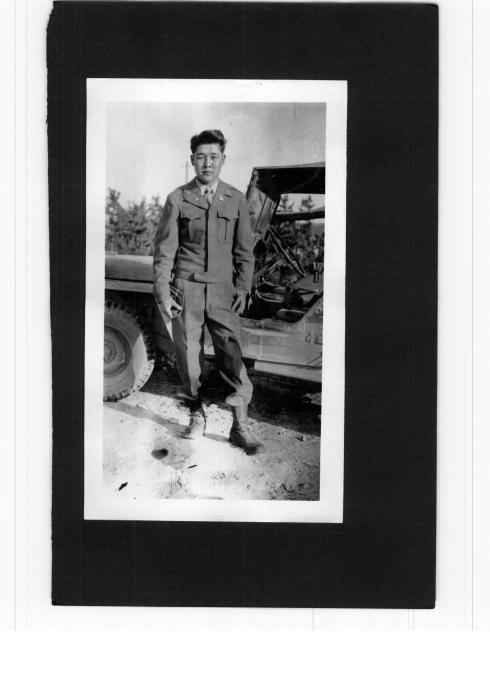

Here’s Uncle Bob, fresh from the military. Just a kid, eh? He always reminded us of Uncle Bill. I don’t really know, but my guess is that Grandpa spoke in the same flat limited register as several of his sons. I feel that I have that voice, too. Uncle Bob died this month; his memorial will be in Hayward in July. You never wanted to go to any family gathering like that—you don’t appear in wedding pictures, group pics. When Uncle Bill died, and I flew back to Los Angeles for the funeral, we took a boat a little ways from the pier to toss his ashes and a few roses into the ocean off Guadalupe Beach. I asked you if you wanted me to pick you up. You said, “Nope, nope. No way. What for? To remember what those people did to each other? What they did to me?” (That’s why you never met or knew Uncle Bob. He was a totally different guy from Bill, even if they looked and sounded remarkably similar.)

It’s true that the violence of racism etched into their characters, some of them, like Uncle Bill’s poisonous anger which he took out on us as children, for others a certain timid smallness of personality, the dutiful attentions paid by other Nisei to assiduous assimilation of Anglo culture. But that wasn’t all there was too it, not by a long shot. They built whole lives of loving and generous care, like you could have.

But they took a shot at making their lives. They came from those margins, from the $25 and one way ticket, one jacket and whatever they could carry with them, and they built new lives. You had your chance at it, like anybody. Your daughter plans to plant a tree on the rec path that overlooks Monterey Bay west of Point Alones, where the Chinese fishing village was burnt out, May 16, 1906. Your daughter wrote a haiku to go on the plaque.

You felt intensely fearful that you wasted your life. Deeply ashamed, you grieved for all lost chances. Women you’d known (who surely have forgotten you and every intimacy and every moment together by now), the family you almost had but now no longer knew you, the life you might have made. The sweetness of these memories shamed you, when you couldn’t stop from thinking about it. That vertigo, teetering between sorrow over what was lost and fear of nothing that lay ahead paralyzed you every day. You screamed at me over the phone, “My problems are not a subject for your poetry!” You didn’t want me to write about you, afraid of that too. Between us, I wrote letters every week to you—and to dad (you were the exact son of the old man).

You rose at 5 AM if you could sleep no longer and went outside in the fleece-lined denim jacket and sat on your porch in the chilly fog, smoking, as dawn rose over the rooftops of the neighborhood. Drinking a first beer.

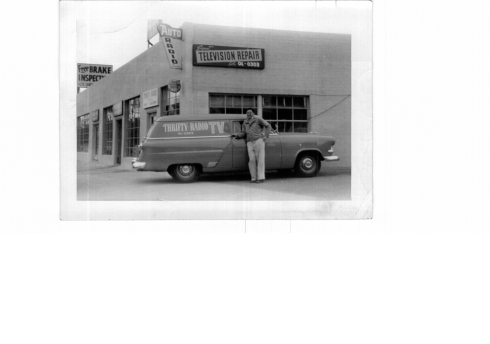

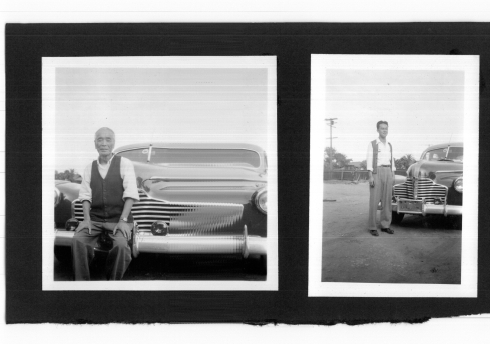

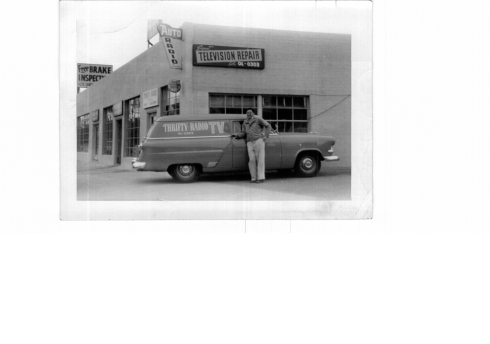

Uncle John’s shop. We never saw it, never went there. We never saw this car with the business name on it either. Like most kids, we never saw the men trade their days away, except that they brought home their largesse, or their wrath.

—-THURSDAY — MARCH 11th, 9 AM cool, sunny.

Yesterday Rick came by, said he’d get back to me Friday. Omar came over and bought me a beer, said he liked the cat drawing. I made us hot Italian sandwiches on fresh white rolls with mushrooms, onions & garlic. Didn’t get much done, some exercise.

Woke this morning feeling bad, worried, cold, almost sick to my stomach.

Yesterday got my food stamps, bought salami, sausage, mushrooms, bread rolls, onions.

Need to be ready to work: Clarity + energy.

MARCH 16 — TUESDAY —bright warmer sun. 9:40 AM

Walked to St. Mary’s yesterday, saw Darlene. Got really exhausted walking up the hill in the heat with a backpack on and my heavy jacket. The farmer’s market was setting up downtown on Lighthouse. (Library closed.)

I didn’t get the job, Tanya called and said they gave it to a guy with a truck, which makes more sense to me, there was lots of hauling to be done. I thought that might happen.

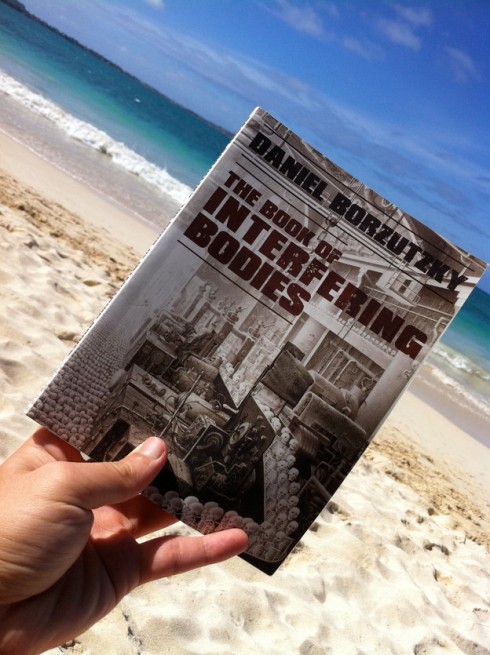

Sesshu sends postcards.

I got to fill out my work search paper for Toni and find out what’s going on with that.

Finally I walked yesterday again. Need to do more of that, get in better shape.

Worked with John on a spaghetti the other day, it came out okay. Want to go to the library, maybe in Monterey.

————-I NEED ENERGY AND CLARITY.

—————–160.00 today (I think)

(Rick did get back to me on Friday, Omar’s been really busy with work so I haven’t seen him much.) Had a good experience reading part of an ORION issue yesterday.

You and dad. Was I the only one who had ever actually known who you had been before you two were destroyed? I felt like I was the only one who knew the “real you.” From before.

You said you once you had walked to the edge of the Bixby Canyon Bridge, but were too afraid to throw yourself off. I stood with you in the sea wind high on the Bixby bridge, the canyon 200 to 280 feet below us. “All right,” I said. “That means there’s time to do something else.”

You told me about a friend who walked out in front of a truck. “They had to pick him up in pieces.” I guess most people have some story like that.

Friends and neighbors loved you, your kindness, gentleness with their kids. They brought plates of food when you were sick. (You had some idea that you would not get well. “Time is almost up,” you said.) Your friends knew “real” you, as much as I did. Omar, drinking himself to death in Oaxaca after being deported (his wife said, weeping for you). When I came to clean out your room (which they had tidied a bit before I arrived), Debbie, Alba and others climbed the flights of stairs to your place. They stood in your doorway, trying to talk to me about you. They looked into my face; they saw that you were not there, either.

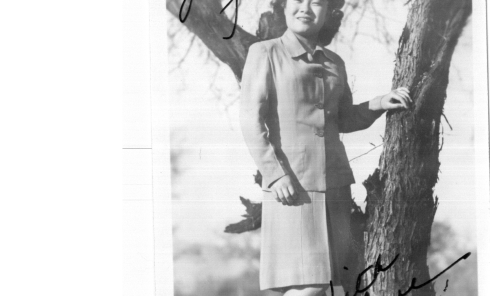

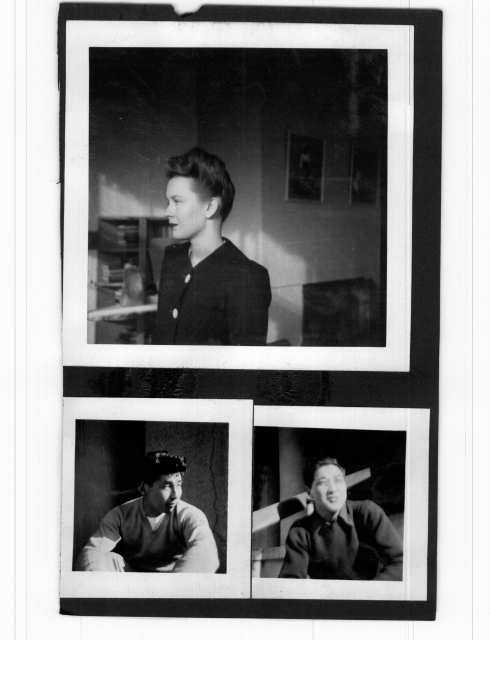

Nobody knows who these friends of John were. “Sadako.” Could she still be alive? He didn’t keep in touch with them. He kept all of these photos from his time at the Fellowship Hostel, from the start of his new life.

John Heygi Agawa, 1920 – 2007.

Tom—named of course for our uncle who died of TB who we never knew—scanned these photographs and threw the originals away; he gave digital files to people in the family.

Fumiko (Karamoto) Agawa, 1924 – 2010

John and Fu met these friends at the Fellowship Hostel (1946?), for a time, forced by circumstance to be neighbors. Then they all dispersed into post-war Southern California. John and Fu married and bought a house on a hilltop in nearby City Terrace.

Like Boyle Heights, it was a mix of Asian Americans, Mexicanos, Jews. The Horis, the Teradas, the Yakushijis, others—some who went to Union Church with John and Fu (in the building that is now the East West Theater Company on Central in Little Tokyo). Uncle Bill bought a house on a hill in City Terrace, too. That was how we ended up in City Terrace.

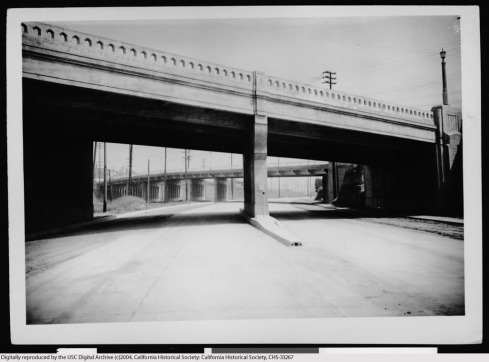

West toward downtown, from Evergreen, down Folsom Street. Your own solitude shamed you. “Sometimes the loneliness is more than I can bear,” you said.

When I told mom at age 90, it staggered her and knocked her back and she said, “When are we going? What can I do?”

“I’m going, Ma,” I said, “but there’s nothing to be done. There’s nothing to be done anymore.”

Sabro and I drove up several times. We cleaned out a couple different apartments for you and tried to set you up so you could have a life. That last time, we emptied out everything. It took the morning. We took stuff to local, thrift stores, where you might have gotten it in the first place. I left John and “John Burke” your pots and pans and kitchenware. I worried a little about throwing too much away, the cassettes of you Zoose from the 1970s or 80s. (Little Omar was very happy to get your computer. Later, I wondered if there photos and documents on it that we might have wanted.) Anyway, I felt it was like the faces we looked into. You weren’t there.

Like a shadow swept from the stairs. Ash tray, empty can at the top of the stairs. Now you’ll never have to be as old as your aunts and uncles, as old as our grandparents, or as old as mom and dad. You’ll never be as old as these photographs.

Dates, names, places, streets, cities, California of dreams.

“To a swell guy— From a Pal— Manuel”

You signed off one of your last letters: “Tick… tick… tick…” and another, “I hope you are well.”

I never felt at home in any of those rooms, the long corridors with the yellow light bulbs, the closed doors. See you in the afternoons on the roadside, in a child in the fields, in a cat on the steps.

Somebody said, you should stop sending him money, or he isn’t going to do anything for himself. I had to wonder if it was any help, year after year, if I was helping save you, or helping destroy you. But I knew it wasn’t only for you. This is something we must do for ourselves, must do as much as we can, or more, for all of us, ourselves.

You were too wrapped up in your own unfolding doom, too trapped in everyday worries and fears to know the story of these people who were part of our lives when we were growing up. You never knew their story. They passed through our lives, and their stories were perfectly smooth, ordinary, unspoken, and therefore unknown. Perfect like a seed.

Who could know us?

Recent Comments