You are currently browsing the category archive for the ‘experimental writing’ category.

This is the ultimate book about Los Angeles because there’s no ultimate book about Los Angeles. There’s no last stop on the L.A. railway whose yellow trolleys went out of service in 1958, there’s no end to Oaxacans, Zapotecs, Mixtecs, Central Americans and Bengalis inventing new lives in Koreatown, no one’s heading to the Ambassador Hotel on Wilshire to disrupt the assassination of Robert F. Kennedy, there’s no end to white hipsters and “creative types” coming to Los Angeles from NYC and points East to make it big, just like there’s no last offramp on the 10 freeway from heading across the desert to Texas and Florida. Which is to say, as the last city of the American civilization before the Pacific Plate subducts under North America and uplifts the ranges of the West, L.A. never stops, it never stops—L.A. never stops. Tropic of Orange dares to go there.

L.A.’s the city at the end of the continent that grinds out industrial daydreams and nightmares for the rest of the planet. “Hollywood will not rot on the windmills of eternity/ Hollywood whose movies stick in the throat of God,” Allen Ginsberg wrote, “Money! Money! Money! shrieking mad celestial money of illusion!” This city industrialized the imagination of the species. This city unspooled reels of Buster Keaton and W. C. Fields, killed Sam Cooke and Janis Joplin, buried Marilyn Monroe and the shadows of ten thousand Indians, Japanese and Vietnamese who dared to attack John Wayne and his cohort of innocents. Driving Route 66 to the edge of the continent, L.A. arrived at the end of the world first. Giant ants, earthquakes, aliens from outer space. The city limits, the Outer Limits. Time and again, even as it was wiped out by Martians in 1953 in War of the Worlds or in 1964 while Charlton Heston drove the empty avenues of downtown in Omega Man looking for vampires to machinegun, the city plowed the civilization’s subconscious and planted alien pod plants.

Roman Polanski’s 1974 noir classic, Chinatown, ostensibly set in 1937, makes no mention, of course, that in 1936 most of Chinatown was razed and buried under the newly built Union Station. Dodger Stadium commemorates in no way the Chicano neighborhood of Chavez Ravine, whose residents were forcibly evicted, whose properties were buried under landfill for baseball parking lots. Entire Japanese American neighborhoods emptied of residents for concentration camps during World War 2: East San Pedro Japanese American residents were given 48 hours to pack and leave—their fishing village then razed, their boats sold or burned. Entire Mexican American neighborhoods were razed and buried under famous freeways. Displacement, dispossession and dislocation continues these days under the guise of gentrification. These are stories that Hollywood can’t seem to imagine, because they’re actually happening. Look in vain for them in Chinatown, Blade Runner, Short Cuts, L.A. Confidential. The ostensibly intergalactic imagination of the movies doesn’t begin to approach hard-bitten realities reflected in the lives of the seven characters central to Tropic of Orange.

Tropic of Orange refracts the city’s passion like skyscrapers against the setting sun. This book holds in solar heat like a piece of granite. Even as the desert east of the San Gabriel mountains refracts the city’s energy like dream lightning in murky dreams of ex-L.A. hipsters gentrified out to Joshua Tree, in sun-bleached dreams of old rock guitarists and rock climbers, as wind scours trinkets of aluminum and plastic across the sand and gravel. Out there across the sand and gravel of his artist’s compound, Noah Purifoy’s human-scale monuments broadcast South Central passion to the cholla, creosote, and the stars. Out there, young black and Latino families from the Marine base shop at the Yucca Valley Walmart. Out there, errant music recorded in L.A. wafts like lost heat waves. Those lyrics, those phrases and rhythms re-emerge inscribed in these sentences, in these chapters. The revolution will not be televised, recalls Tropic of Orange on page 218, even as a romantically entangled Chicano and Japanese American couple, journalists, tragically try to prove it wrong.

If L.A. is that recombinant hybrid of the culture’s imagination and the civilization’s final history, of its weird and frequently terrible desires taken to their ultimate logical ends (freeways and car culture, cults and crazies, a police state hidden behind sunglasses and sun-tans), few novels live to tell actual Los Angeles stories and effectively take anything like its full measure. Tropic of Orange takes that apocalyptic tale on with Surrealist nerve and Futurist verve. Karen Yamashita looks on what the civilization wrought on this place, unafraid—she doesn’t turn away; five years after the 1992 riots (“the largest civil disturbance in modern times… 60 dead, one billion dollars damage…“), columns of smoke still rise from those conflicts of race and class. Seven voices, each distinguished by a distinct voice and POV, tell stories that sojourn the Pacific, traverse the Sonora Desert, cross mean streets and ethnic divides to meet, folding into one another in a wild (and wildly imagined) 7 days in Los Angeles.

In 2011, as visiting professor of creative writing at UC Santa Cruz, I wandered into the lunch counter at a cafe that Karen liked, and found her hosting a party of out of town visitors. She invited me to join them, and as I pulled up a chair, one of the visitors, Robert Allen, was talking about the Port Chicago mutiny, the largest mass mutiny in U.S. naval history, when 50 black sailors were court-martialed in 1944 after 700 men were blown apart (320 died) loading munitions aboard ships heading for the war in the Pacific. “Robert!” I said, jumping up, “you’re the only person I’ve ever heard talking about Port Chicago!” I ran over and gave him a hug. “The last time I saw you was in Nicaragua! How long has it been? Twenty years?” He’d written a book about Port Chicago and edited the Black Scholar journal for decades. I’d only learned about Port Chicago more than twenty years earlier and more than three thousand miles away, in Managua, in 1987, when Robert told me about it as we sat at a table with Alice Walker. I’ve only heard the story of Port Chicago twice in my life, both times by luck, the kind of luck and the kind of stories you get when Karen Yamashita invites you to sit at her table. Tropic of Orange invites you; try your luck—you’re in for seven kinds of L.A. stories that fold into an origami flower of razor-sharp titanium.

Sesshu Foster

see:

The Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center hosted “CrossLines: A Culture Lab on Intersectionality” at the Smithsonian’s historic Arts and Industries Building Saturday and Sunday, May 28–29, 10 a.m. to 9 p.m., in celebration of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. Featuring the works of more than 40 artists, scholars and performers, “CrossLines” exhibited array of art installations, live performances and interactive maker spaces.

Lawrence-Minh Bùi Davis said, “We had a “poetry listening salon” with an iPad station set up with the video as well as several audio poems–by Juan Felipe Herrera, Arlene Biala, Rigoberto Gonzalez, Brandon Som, and Tarfia Faizullah. Response was great; 12,000 people came through the event, and a lot of people sat in the salon and used the station.”

At the de-installation of the exhibit, Lawrence sent this picture of Clement Hanami and Sojin KIm checking out the video by Arturo Romo-Santillano of a poem of mine, “Hell to Eternity: The Movie Version.”

See: http://parrafomagazine.com/issues/06/foster/movieversion.html

Clement Hanami and Sojin Kim

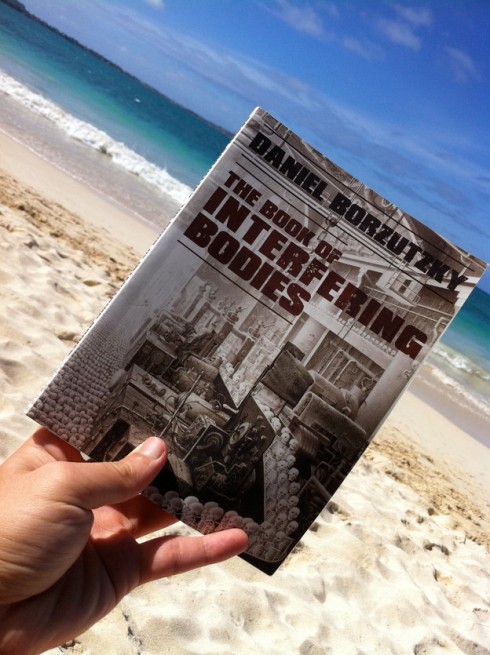

2011, Nightboat Books

THE BOOK OF FORGOTTEN BODIES

The reader who opens the Book of Forgotten Bodies finds nothing. There are no horses galloping through deserted villages in search of the men who used to ride them. There are no children crying for their parents who were thrown out of airplanes and into the sea. There are no soldiers who had their arms sliced off for refusing to obliterate innocent bodies. There are no rich men leaning against paradise trees as the drunk bodies of poor men stumble up to their houses to kill them. There are no bodies of hopeless virgins smashes on city streets by Mercedes-Benzes cruising through the gentle drizzle of a foggy day. There are no bodies abandoned on beaches. There are no corpses floating down rivers. There are no bodies hanging in the military barracks on island XYZ off the coast of nation ABC. There are no bodies that pound rock against rock. No bodies that stand on one leg with hoods over their mouths mumbling words we don’t understand. No bodies covered in mud murmuring to the bodies that lie on top of them. There are no bodies that smell of chemicals and rest in puddles in the rain waiting for flowers to fall on their heads. No blind bodies that are painted by artists who value aesthetics over breath. No bodies that imagine their children’s bodies as ghosts and cadavers and skeletons. No bodies that fall from windows as they try to catch a glimpse of the bodies that have fallen before them. There are no bodies discovered by rabid dogs in houses abandoned before they could even be built. No bodies surrounded by barbed wire as countries die in the distance. No bodies whose skin burns in the strange machines that buzz like tropical nights. No bodies that burn in buildings that have been set on fire by bodies with no reason to live. There are no bodies that fry in the sun, that drown in the shadows, that roast on gas, that ooze algae and moss, that are covered in black rags as the lakes and the mountains die. No bodies that hunt or are hunted, that murder out of charity, that are murdered out of charity. No bodies that shutter the windows and hang themselves in libraries of their favorite books. There are no soulless bodies, no frozen bodies, no bodies gnawed to death by insects. There are no practice bodies, no transient bodies, no empty bodies, no blank bodies that twist between forgotten body and dream.

see also http://jacket2.org/commentary/talking-daniel-borzutzky

and, http://entropymag.org/are-we-latino-memories-of-my-overdevelopment/

ONE SIZE FITS ALL

See that immigrant freezing beneath the bridge he needs a blanket.

See that torah scroll from the 16th century: it sprawls on the floor like a deadbeat; the Jews need to wrap it in a schmatte.

The problem, you see, is “exposure.”

Thje poet forgot to shake off his penis and pee dripped on the manuscript that he submitted to the 2007 University of Iowa Poetry prize.

The literary scholar took off his tie and lectured the class on the post-humanoid implications of the virtual cocktail.

He put a pistol on his desk and told the students he was going to kill himself if they didn’t do their homework.

Everything in his “worldview” was exposed.

The data-entry specialist imagined new forms for the senior administrator who was only a temporary carcass, an anti-poem: a budding literary movement that communed with master works by committing suicide while reading them.

The temporary carcass of the bureaucrat, dry as Vietnamese Jerky, called out for “gravy” as it “peppered” the eloquent field of syntax.

Abrupt exposure to ordinary language may result in seriously compromised intelligence, implied the carcass as he lipped the trembling lily which hid the police officer, who said: if you look at me one more time I’m going to zap you with my Taser gun.

I liked the former “Language Poet” for the speech act he attached to the back of my book, which reminded me of Charles Olson on human growth hormones.

The problem, said the critic, remains one of imagination and its insistence on the distinction between thought and action.

“I let him touch my wooden leg,” she said, “and when I unscrewed it I was stuck legless in the hay.”

Which is to say the detachable penis was and has been compatible with family values.

“He was a seriously hardworking boy with a fetish for glass eyes and wooden legs,” she said, “and I really loved him.”

The poetry era reached its nadir as the housing market plummeted, said the professor, as he repeated for the umpteenth time the anecdote about the boy who met an underwater woman as old as the hills.

“Does Poetry live here,” he asked. “Poetry lives here,” she replied, “but he will chop you up and kill you, and then he will cook you and eat you.”

My ideal reader has neither a name, a body, nor an online profile.

Which is not to say that I am not concerned with customer satisfaction.

Dear Reader, Because we value your input, please take a moment of your busy time to answer the following question, which will greatly assist us in our mission to produce cultural artifacts that will further meet your aesthetic and spiritual needs.

Which of the following statements most accurately reflects your feelings about the writing which you have just read:

a. This is a splendid poem, distinguished by the clarity of its thought, the force of its argument, and the eloquence of its expression.

b. This poem is conceptually vapid, artistically shallow, and contributes nothing to the world of letters. It is little more than a collection of bad sentences and poorly formed ideas.

c. I like this poem, but I wouldn’t spend money to read more poems like it.

d. When I read this poem, I feel frustrated and annoyed.

e. When I read this poem, I feel nothing.

glad we could talk, my students came and enjoyed it—

later, i read some poems with Kenji Liu and Angela Peñaredondo

at the Kaya Press tent, and afterwards went round and caught

your reading at the poetry stage, where I saw the call

and response of “187 reasons mexicanos can’t cross the border”

caused passersby to stop in their tracks, turned their heads; they

drew forth under the trees to see what you were delivering

from the stage. this was before you closed, zapateando.

i should have joined you when they took you to sign books.

it started sprinkling, as it had been on and off all day

and like i had been, i was thinking about the lean girl,

my student who died two weeks ago, swept out by a wave

at santa monica beach, in sight of the pier and surely crowds

of hundreds of people on an ordinary saturday afternoon,

drowned. now there’s nothing to say about it, nothing to be done,

so i wandered through the tents, looking at the booths

full of books and booksellers, writers and readers, and

when i figured that we maybe still had time to talk,

i went back to “the green room” but i couldn’t locate

you—i did a circuit, walking through the crowd and the tents

in the off and on again drizzle, talked to David Shook

at Phoneme Books, bought his translations from the Zapotec,

i guessed soon you’d have minders escorting you onstage

at the award ceremony, though i could have let loose

the dogs of metaphor or raised a figurative hue and cry

as of metonymy, but let the mist in the air settle as it may.

thanks for the hour or more. let’s talk again! maybe

i’ll see Fresno, capital of poetry. hi to Margie!

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

L.A. TIMES FESTIVAL OF BOOKS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA

http://events.latimes.com/festivalofbooks/tickets-and-schedule/schedule/

Seeley G. Mudd (SGM 123)Ticket required; Signing Area 4

| 11:30 a.m. |

SATURDAY, APRIL 9, 2016 Juan Felipe Herrera in conversation with Sesshu Foster Interviewer: Sesshu Foster |

Juan Felipe will also be reading at the festival’s Poetry Stage at 2:30 PM

Indoor Conversations require free tickets.

There are two ways to get Conversation tickets:

Online

Advance Conversation tickets will be available from the website starting April 3, 9 a.m. A $1 service fee applies to each ticket. See http://events.latimes.com/festivalofbooks/tickets-and-schedule/ticket-info/

At the festival

A limited number of tickets for each Conversation is distributed at the festival ticketing booth on the day of the Conversation — free of service charges. The booth will open at 9 a.m. each day.

Guests with Conversation tickets must arrive 10 minutes before the scheduled Conversation start time to ensure seating.

a poem by Juan Felipe:

latest book:

http://www.citylights.com/book/?GCOI=87286100437770&fa=author&person_id=4859

Blood on the Wheel

Ezekiel saw the wheel,

way up in the middle of the air.

TRADITIONAL GOSPEL SONG

Juan Felipe Herrera, “Blood on the Wheel” from Border-crosser with a Lamborghini Dream. Copyright © 1999 by Juan Felipe Herrera. Reprinted by permission of University of Arizona Press.

Source: Border-crosser with a Lamborghini Dream (University of Arizona Press, 1999)

Jen Hofer

on / with Antena / Antena Los Ángeles

presents:

¡El AntenaMóvil ya está instalado! Ven a nuestro evento bilingüe este sábado no solamente para compartir comida rica y conversación rica, sino también para ver/leer/comprar libros de muchas editoriales pequeñas y micros de Latinoamérica y Estados Unidos — incluyendo las maravillas locales Kaya Press, Phoneme Media, Ricochet Editions, Seite Books, y Writ Large Press. El Antenamóvil es un triciclo de carga adaptado, equipado con libros que están a la venta y para leer aquí. La selección se enfoca en obras bilingües y multilingües, textos en traducción y textos innovadores de escritorxs de razas marginadas.

¡The AntenaMóvil is installed! Come to our bilingual event this Saturday not just to share delicious food and delicious conversation, but also to see/read/buy publications from many small and micro presses from Latin America and the U.S. — including local wonders Kaya Press, Phoneme Media, Ricochet Editions, Seite Books, and Writ Large Press. The AntenaMóvil is a retrofitted Mexican cargo trike stocked with books that are for sale and for reading on-site. The selection features bilingual and multilingual works, work in translation, and innovative texts by writers of color.

Justicia laboral alimentaria + Justicia del lenguaje: Un intercambio bilingüe

Food Labor Justice + Language Justice: A Bilingual Exchange

con / with Antena / Antena Los Ángeles, Cocina Abierta & ROC-LA

12 marzo / March 12

12pm – 3pm

Gratis / Free

Se proporcionará comida, pero si deseas, ¡trae una receta o un plato para compartir!

Food will be provided, but if you like, bring a recipe or a dish to shar e!

https://hammer.ucla.edu/antena12marzo/

Por favor RSVP / RSVP Please

(¡pero ven aunque no puedas RSVP! / ¡but come even if you can’t RSVP!)

Hammer Museum

10899 Wilshire Blvd

Los Angeles CA 90024

The Worker Body / El cuerpo trabajador, Cocina Abierta & ROC-LA, July 2015 / julio de 2015.

Photo/Foto: Heather M. O’Brien

Antena y Antena Los Ángeles, artistas en residencia con el programa de Public Engagement (Participación pública), junto con artistas, organizadorxs y trabajadorxs restauranterxs de la colectiva Cocina Abierta y El Centro de Oportunidades para Trabajadores de Restauranterxs de Los Ángeles (ROC-LA), invitan a lxs visitantes del Hammer a compartir comida, ideas y conversación en un espacio bilingüe. Les invitamos a escuchar las historias de trabajadorxs restauranterxs y posteriormente participar en un diálogo bilingüe durante una comida estilo familiar. Se proporcionará la comida, pero cualquier plato o receta que quieran traer será bienvenido.

¡Colabora compartiendo una receta para nuestro recetario!

Las recetas que logre recolectarse serán utilizadas por Libros Antena Books para crear una pequeña publicación DIY (Do-It-Yourself o hazlo-tú-mismx), que será distribuida a todxs lxs participantes.

Public Engagement artists-in-residence Antena and Antena Los Ángeles, along with artists, organizers and restaurant workers from the Cocina Abierta collective and Restaurant Opportunities Center of Los Angeles (ROC-LA), invite Hammer visitors to share food, ideas, and conversation in a bilingual space. Visitors are invited to hear the stories of restaurant workers and afterward engage in bilingual dialogue over a family-style meal. Food will be provided, but feel free to bring a dish or recipe to share.

Participate by contributing a recipe for our recipe book!

The collected recipes will be made into a small DIY publication by Libros Antena Books and distributed to all participants.

Jen also notes, NEWLY AVAILABLE:

¡Ya salió la traducción de Estilo (Style) de la feroz escritora mexicana Dolores Dorantes! Puedes comprar el libro en Small Press Distribution o directo de Kenning Editions .

My translation of Estilo (Style) by the fierce Mexican writer Dolores Dorantes is out! You can by the book from Small Press Distribution or directly from Kenning Editions .

https://gorskypress.bandcamp.com/track/sesshu-foster-reads-new-and-old-poems

In front of a live audience at Book Show on October 30, 2015 in Los Angeles, CA as part of Vermin on the Mount, an irreverent reading series hosted by Jim Ruland.

an annual anthology of the best new experimental writing

BAX 2015 is the second volume of an annual literary anthology compiling the best experimental writing in poetry, fiction, and creative nonfiction. This year’s volume, guest edited by Douglas Kearney, features seventy-five works by some of the most exciting American poets and writers today, including established authors—like Dodie Bellamy, Anselm Berrigan, Thomas Sayers Ellis, Cathy Park Hong, Bhanu Kapil, Aaron Kunin, Joyelle McSweeney, and Fred Moten—as well as emerging voices. Best American Experimental Writing is also an important literary anthology for classroom settings, as individual selections are intended to provoke lively conversation and debate. The series coeditors are Seth Abramson and Jesse Damiani.

Guest editor DOUGLAS KEARNEY is a poet, performer, and librettist. He is the author of Patter and The Black Automaton. He lives in Los Angeles. SETH ABRAMSON is a doctoral candidate at the University of Wisconsin–Madison and author of five books, including Thievery, winner of the Akron Poetry Prize, and Northerners, winner of the Green Rose Prize. He will be teaching at the University of New Hampshire in the fall. JESSE DAMIANI was the 2013–2014 Halls Emerging Artist Fellow at the Wisconsin Institute for Creative Writing and has received awards from the Academy of American Poets and the Fulbright Commission. He also lives in Los Angeles.

here’s a link to the issue’s digital content:

blurbs:

“The permission is on every page here. The best annual experience where space is held for radical experimentation is in this book. Thanks to the editors for really keeping it real.”—CA Conrad, author of Ecodeviance

“Whether oath, tweet, conspiracy simile, or tour of Hummeltopia, this anthology swings with verve and nerve from CM Burroughs’s ‘juncture of almost’ to Roberto Harrison’s ‘contaminate network of paradise.’ The experiment lives! It exists, Lance Olsen writes, ‘the same way, say, future dictionaries exist.’”—Elizabeth Robinson, author of On Ghosts

$19.95 Paperback, 978-0-8195-7608-8

$40.00 Hardcover, 978-0-8195-7607-1

$15.99 Ebook, 978-0-8195-7609-5

Contents

• Guest Editor’s Introduction, Douglas Kearney

• Series Editors’ Introduction, Seth Abramson and Jesse Damiani

• Will Alexander, To electrify the abyss from The General Scatterings and Comment

• Steven Alvarez, tape 3

• Emily Anderson, from “Three Little Novels”

• Aaron Apps, The Formation of This Grotesque Fatty Figure

• Dodie Bellamy, Cunt Wordsworth from Cunt Norton

• Anselm Berrigan, rectangle 71

• Jeremy Blachman, Rejected Submissions to “The Complete Baby Name Wizard”

• Shane Book, Mack Daddy Manifesto

• CM Burroughs, Body as a Juncture of Almost

• Rachel Cantor, Everyone’s a Poet

• Xavier Cavazos, Sanford, Florida

• Ching-in Chen, bhanu feeds soham a concession

• Cody-Rose Clevidence, [X Y L O]

• Cecilia Corrigan, from Titanic

• Santino Dela, This is How I Will Sell More Poetry Than Any Poet in the History of the Poetry – Twitter Feed (The YOLO Pages)

• Darcie Dennigan, The Ambidextrous

• Steven Dickison, from Liberation Music Orchestra

• Kelly Dulaney, Incisor / Canine

• Andrew Durbin, from You Are My Ducati

• Thomas Sayers Ellis, Conspiracy Smile [A Poet’s Guide to the Assassination of JFK and the Assassination of Poetry]

• Bryce Emley, The Panthera tigris

• Adam Fitzgerald, “Time After Time”

• Sesshu Foster, Movie Version: “Hell to Eternity”

• C. S. Giscombe, 4 and 5 from “Early Evening”

• Renee Gladman, Number Two of the Eleven Calamities

• Maggie Glover and Isaac Pressnell, Email Exchange – Like a Flock of Tiny Birds

• Alexis Pauline Gumbs, “Black Studies” and all its children

• Elizabeth Hall, from “I Have Devoted My Life to the Clitoris: A History of Small Things”

• Brecken Hancock, The Art of Plumbing

• Duriel E. Harris, Simulacra: American Counting Rhyme

• Roberto Harrison, email personas

• Lilly Hoang and Carmen Giménez-Smith, from Hummeltopia

• Cathy Park Hong, Trouble in Mind

• Jill Jichetti, [Jill Writes . . .]

• Aisha Sasha John, I didn’t want to go so I didn’t go.

• Blair Johnson, The overlap of three translations of Kafka’s “Imperial Message” – I consider writing (a love poem)

• Janine Joseph, Between Chou and the Butterfly

• Bhanu Kapil, Monster Checklist

• Ruth Ellen Kocher, Insomnia Cycle 44

• Aaron Kunin, from “An Essay on Tickling”

• David Lau, In the Lower World’s Tiniest Grains

• Sophia Le Fraga, from I RL, YOU RL

• Sueyeun Juliette Lee, [G calls] from Juliette and the Boys

• Amy Lorraine Long, Product Warning

• Dawn Lundy Martin, Mo[dern] [Frame] or a Philosophical Treatise on What Remains between History and the Living Breathing Black Human Female

• Joyelle McSweeney, “Trial of MUSE” (from Dead Youth, or, The Leaks)

• Holly Melgard, Alienated Labor

• Tyler Mills, H-Bomb

• elena minor, rrs feed

• Nick Montfort, Through the Park

• Fred Moten, harriot + harriott + sound +

• Daniel Nadler, from The “Lacunae”

• Sunny Nagra, The Old Man and the Peach Tree

• Kelly Nelson, Inkling

• Mendi + Keith Obadike, The Wash House

• Lance Olsen, dreamlives of debris: an excerpt

• Kiki Petrosino, Doubloon Oath

• Jessy Randall, Museum Maps – Dominoes

• Jacob Reber, Deep Sea Divers and Whaleboats – Camera and Knife

• J D Scott, Cantica

• Evie Shockley, fukushima blues

• Balthazar Simões, [Dear Emiel]

• giovanni singleton, illustrated equation no. 1

• Brian Kim Stefans, from “Mediation in Steam”

• Nat Sufrin, Now, Now Rahm Emmanuel

• Vincent Toro, MicroGod Schism Song – Binary Fusion Crab Canon

• Rodrigo Toscano, from Explosion Rocks Springfield

• Tom Trudgeon, Part 2/21/6 from Study for 14 Pieces for Charles Curtis

• Sarah Vap, [13 untitled poems]

• Divya Victor, Color: A Sequence of Unbearable Happenings

• Kim Vodicka, U n i s e x O n e – S e a t e r

• Catherine Wagner, Notice

• Tyrone Williams, Coterie Chair

• Ronaldo V. Wilson, Lucy, Finally

• Steven Zultanski, from Bribery

• Aaron Apps, “You are only a part of yourself, collected in tangles”

• Matthew Burnside, In Search of: Sandbox Novel

• Alejandro Miguel Justino Crawford, Egress

• Lawrence Giffin, from Non Facit Saltus

• Tracy Gregory, For Mercy

• Tina Hyland, Google the Future

• Kaie Kellough, creole continuum – d-o-y-o-u-r-e-a-d-m-e

• Joseph Mosconi, from Demon Miso/Fashion in Child

• Dustin Luke Nelson, [Everything That Is Serious Can Have a Filter]

• Jeffrey Pethybridge, Found Poem Including History

• Acknowledgments

• Contributors

for sale at http://www.upne.com/0819576071.html

As gentrification sweeps the city, Sesshu Foster has quietly become the poet laureate of a vanishing neighborhood

LOS ANGELES — In this high-turnover city, the Eastside, more than the moneyed west, has seemed to hold on to its past. There are eccentric bungalows and blanched murals, and shopping corridors with the foot traffic and feel of a village market. Neighborhoods such as Lincoln Heights, El Sereno and City Terrace have thus far escaped the peculiar affliction of the upscale coffee shop. Their residents and business owners are still predominantly Latino and Asian, and largely working class — though perhaps not for long. According to trend-spotters, East LA is the molten core of gentrification, full of hipsterpreneurs with backing from friends in venture capital.

To see the real Eastside, ask the writer and teacher Sesshu Foster to take you on a little tour. He’ll pick you up downtown in his Toyota SUV, air conditioner whooshing, a Ry Cooder track pulsing. You’ll cross the LA River — thin puddles in a long concrete ditch — and keep going down Cesar Chavez, originally named Brooklyn Avenue by Jewish émigrés. Every few blocks, you’ll glimpse a faded mural and Foster will explain the story behind each one. If there’s graffiti, he’ll denounce the taggers’ “total disregard for their grandparents’ social art” in his unhurried Angeleno drawl.

Foster, 58, the author of four award-winning books of poetry and prose, is an encyclopedist by nature, the Diderot of the neighborhood. His writing is political, experimental and consistently local, even unfashionably so. A family man and full-time public school teacher, he’s never focused on self-promotion, yet he is praised within literary circles and counts U.S. poet laureate Juan Felipe Herrera, novelist Karen Tei Yamashita and poets Claudia Rankine and Amy Uyematsu among his friends and peers. Herrera says Foster might be better known if not for the day-to-day “pressure [on] working-class writers, writers of color… writing for the community.”

The project currently on Foster’s mind is a multimedia, quasi-fictional history of East LA, which he’s compiling with his friend, artist Arturo Ernesto Romo-Santillano. Their research includes a lot of driving, walking, looking and talking, and so in March the three of us drove to Boyle Heights and parked in view of the Sears tower, an Art Deco complex slated for mixed-use redevelopment. We’d come to see the murals on the Estrada Courts, a grid of two-story public housing. “The Chicano movement always had artists as cultural ambassadors,” Foster said, gesturing at some their creations.

We passed walls depicting a pointing Che Guevara and a haloed Jesus on our way to the “Black and White Mural” by the renowned Chicano collective ASCO. In humble monochrome, abstract scenes from the Chicano Moratorium, the radical, Mexican-American movement against the Vietnam War, read like frames in a strip of film. Like ASCO, Foster and Romo-Santillano see their approach to art making as “by and for the people.” In a city “where everything gets constantly built over,” Foster described their experimental history of East LA — already more than five years’ work — as an attempt at salvage.

East LA is Foster’s assembly and holy land, where he was raised and where he raised his three daughters. Not far from the home he shares with his wife, Dolores Bravo, is the house in City Terrace that he and his six siblings grew up in, and where his mother, a 90-year-old second-generation Japanese American, still lives. She brought the kids to the neighborhood after leaving their father, an Anglo painter who was thudding his way through the Beat era.

The Eastside that groomed Foster in the 1960s and ’70s has little in common with the polished, commercially cool destination featured on food blogs or portrayed on “Maron,” comedian Marc Maron’s sitcom. As a kid in City Terrace, a rough neighborhood prone to violence, Foster neglected school and ran the streets with a Chicano gang, avoiding his abusive uncle and the chaos of home. Though he is hapa, half-Japanese and half-white, he came of age in a Mexican American milieu, at the cultural and political peak of Chicano activism.

Since his teenage years, Foster has had an unwavering partner. He met his wife, an East LA Chicana, on a high school science trip and just kept “following Dolores,” says his cousin Tom Ogawa. In college, Foster stayed tied to Bravo while bouncing from one University of California campus to another. His jobs were as varied: In Palo Alto, he was a strip-club bouncer; in Colorado, a summer firefighter — the best gig he’s ever had, he says. “I was reading Mao, Stalin, Che Guevara, anybody, Carey McWilliams or novels or whatever and waiting around for fires. And then you get called out on fires… There’s a certain element of risk to keep you on your toes.” He only quit on account of their firstborn, Marina, who arrived when his wife was a graduate student in Seattle. “I wasn’t going to do what my dad did, which was never be there.”

Above: A sampling of the dozens of postcards Foster has sent to penpals in 2015. Mouse over the cards to view the opposite side.

After Marina came Umeko, then Lali — three daughters spaced almost 12 years apart. The girls were raised on their parents’ schoolteacher salaries, first in a house near City Terrace, then in Alhambra. Between his work schedule and young children’s needs, writing became a jigsaw, which was just as well for someone who refused to be “a lonely poet writing in an attic, starving.” There were unclaimed minutes here and there, around the edges of family, teaching and the teachers’ union. On Saturdays, Bravo gave Foster time to write. Summer breaks were sacred.

Foster’s craft is inseparable from his day job and family: “None of the work I’ve done would have been done without our collectivity,” he says. In his most recent volume, “World Ball Notebook” (City Lights 2008), he presents a collection of numbered “games” that allude to his daughters’ soccer matches as much as his own wordplay. One of my favorites, Game 114, reads in part:

the mayans failed, civilization collapsed.

dinosaurs failed, became birds.

the sun went down, came up on a foggy day.

the moon failed, so shut up.

dirt failed came out in the wash.

your mom failed, look at you, kid.

In 1994, on the heels of heated union talks, Foster, Bravo and the girls, then ages 2, 9 and 13, decamped for Iowa City and the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. It was the nation’s most revered MFA program and a Midwest respite from the chaos of LA. By that time, he had already co-edited an anthology of poets of color, “Invocation LA” (West End Press, 1989), and published a book of poems, “Angry Days” (West End Press, 1987), which bears the characteristic tensions in his work: the funny, grotesque and polemical, on the one hand (“agribusiness required a constant surplus / with wages controlled”); a gentleness and naturalism on the other (“little halfmoons of dirt / wax underneath my fingernails). As someone who zigzags between poetry and prose, Foster turned out to be a poor stylistic fit for Iowa. “He was different from the other students,” says Warren Liu, a former classmate and a professor of English at Scripps College. “He wasn’t out to prove anything to anyone.”

By the end of this MFA, a poetry project long in the works was set for release. “City Terrace Field Manual” (Kaya, 1996), Foster’s most popular collection, is a paean to the East LA of his childhood. Published by a small press specializing in the Asian diaspora, the stanzas are rich with references to local landmarks and people: the Santa Ana Freeway, Arthur Buell, Priscilla, Highland Park, Chemo, Xochitl, Manny, El Sereno, Areceli Cruz and Wanda Coleman. After two years in the Iowa snow, Los Angeles beckoned:

I would dream about City Terrace and

my friends in East L.A. They kept coming back, talking

to me … the same old things.

The success of “City Terrace Field Manual” might have tempted another writer to shake off his geographic fixation. Foster, though, wasn’t yet done documenting East LA. “This is what I’m going to do because who else is going to do it?” he says. “Even Chicanos who want to do it don’t do it. [Representing the community] is one of my principal tasks.”

In his basement study, as on countless pages and screens, Foster is an artist of accumulation. He says Facebook deactivated his first account, mistaking him for a spamming robot. He’d posted too many aphoristic scribbles and links to articles — about education, Mexico, Palestine, poetry, capitalism, the immigrant rights movement and criminal justice, to mention a few. He’s constantly blogging, sending emails and participating in poetry readings and political fundraisers. “He’s a worker,” says artist and fellow teacher Romo-Santillano. “Being an artist is about working.”

Foster is prolific on paper as well, particularly when he’s in epistolary mode. He grew up exchanging letters with his dad, a Dharma bum on the road. “That was really our basic, tangible relationship, one of correspondence,” he says. These days, he mails up to 20 postcards a week, inked with grocery lists, diary entries, dialogues and literary family trees in arty spirals of red. Lisa Chen, a Brooklyn-based writer who met Foster at Iowa, estimates that she’s received well over a thousand of his postcards since the mid-1990s. Her fridge is covered in them. “It’s a form of diary or journaling, reflection — and also a way of saying ‘hi’ to people far away,” Foster explains. He delights, too, in how postcards allow for an “often arbitrary juxtaposition” of image and text: “I don’t think in linear, standardized, ‘First they woke up. Then they walked out the door,’” he says. “Things come to me out of order.”

The same might be said of his books, which resist a neat progression from one to the next. “City Terrace Field Manual” raised Foster’s profile and helped define him as an Asian American poet, yet his next volume would be an avant-garde “Chicano” novel. “Atomik Aztex” (City Lights 2005), which won the Believer Book Award, imagines the life of a slaughterhouse worker in an un-colonized America; the prose is shot through with invented dialects and pages-long paragraphs in italicized script. “It was sort of hard on purpose,” Foster says. “I was in that mood.” The language is by turns zany and brutal, especially in the slaughterhouse scenes: “Esophagus tracts raw from chlorine… The sky might already be lightening, backlit that cool electric blue.” It’s a futuristic Aztec civilization — the indigenous people now ascendant — yet still oppressive, empire all the same.

In any other city, and in any neighborhood besides East L.A., it’s unlikely that a half-Japanese, half-Anglo poet would be so enmeshed in Chicano cultural production. “His culture is L.A. culture, which is fluid; a mishmash,” says Chen. “His Spanish is better than his Japanese.” Herrera calls him “a sci-fi Argentinian. He’s like Borges.”

To be biracial or mixed race is to be permanently neither. It’s also distinctly Angelean, says Ruben Martinez, a professor at Loyola Marymount University: “Sesshu’s mixed parentage and geographical weaning in East LA made him, like, post-Mestizo.” Because of this, Foster worries that his oeuvre has a narrow reach. “Being mixed — that never puts you in solid with one group. That means you’re always kind of on the border, you’re on the margin, one or the other. Inasmuch as my work plays to Asian Americans and Chicanos, that’s the minor leagues,” he says, adding, “If I’m not doing some crossover thing with white people, I’m always going to be [minor].”

To those familiar with his work, however, Foster is vital; one of the “iconic voices writing from Los Angeles,” says Elaine Katzenberger, his editor at City Lights, the bookstore and publisher founded by beatnik Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Like everyone interviewed for this story, Katzenberger spoke of his unassuming industriousness — “as a teacher and activist [he’s] making all kinds of cultural connections, but he’s such a quiet presence, not tooting his own horn.” Foster’s rootedness also sets him apart, says journalist Ben Ehrenreich, who befriended him while writing about “Atomik Aztex”for the Village Voice. “He’s extraordinary today in his quiet, humble insistence that writers can and ought to relate to the world around them [in a way] that’s not just dictated by the market, agents and MFA posts — that whole world of bullshit.”

Foster’s commitment to write about the world he sees is matched by an equal impatience for the commercial cultural establishment attempting to whitewash it. Last September, just before the closing of “Made in L.A. 2014,” a biennial exhibition at UCLA’s Hammer Museum, he paid a visit with his wife and mother, who trained as a painter. The show featured 35 LA-based visual artists, mostly young and “emerging,” working in photography, video, painting, performance, installation and sculpture. Foster was unimpressed by what he saw, in part because his companions were so disappointed; alienated, in fact, from the purported art of their city.

He went home and wrote a poem about the experience, posting it to the blog he’s maintained since 2008. Like much of what he writes, this was a textual doodle; aesthetic and institutional critique in a lowercase, stream-of-consciousness style:

it’s okay that the artists are all white, even the nonwhite artists (2?) are kind of white

it’s okay that the curators are all white …

it’s all right because the ucla hammer museum curated and hosted ‘now dig this! Art and black los angeles 1960 – 1980’ which exhibited from october 2011 to january 2012

so it’s okay, because ‘black los angeles’ had its day …

it’s okay that the apartheid imagination remains in place and is not disrupted

thank you

His real target was “racism in the institutions of LA,” Foster explains. And the blog post went viral, provoking an extended debate within the city. Even those aligned with Foster accused him of being too prescriptive and orthodox. In the Los Angeles Review of Books, writer Nikki Darling pointed out that 11 artists of color had been part of the Hammer biennial and criticized Foster for “expecting artists of color to produce work that explicitly addresses identity.”

Foster stood by his critique. The blog post was not journalism; it was a poem, he says. And it did what so few poems do: spark controversy.

In the weeks following, a local art space hosted “decolonizing the white box,” a public forum inspired by his post. More than 150 people turned out; there had been a hunger for conversations about race in the art world. “His work was able to draw out such ire and tension,” says Raquel Gutierrez, the young poet and activist who moderated the event. Foster is “very terse in his online presence and his work,” she said, but he is “our [Juan Felipe] Herrera, [Sandra] Cisneros, Junot Diaz, [a writer] who endured the whiteness of the MFA machine and raged against that machine.”

Foster has always seen words as “adjunct to political activity.” He never wanted his fiction or verse to exist only in a white box, far from the street. “I’m politically involved in the things I write about,” he says, “and my politics are informed by actual experience, not just things I saw on the news.”

His work can be incredibly funny, as he is in person, but it’s also sincere and serious in purpose, much like the Chicano murals painted during his youth. His fondness for that era’s art leaves him open to accusations of being retrograde, an “identity politician.” Yet Foster’s work isn’t “preachy,” says Lauri Ramey, director of the poetry center at Cal State LA. “The aesthetic sensibility of his work serves his ethical vision. … That’s what keeps it from feeling like a polemic.”

At some point soon, in some form resembling a book, City Lights will publish Foster’s collaboration with Romo-Santillano: a multi-genre assemblage premised on a fictional corporation, East Los Angeles Dirigible Transport Lines. Borrowing from the Beats as much as Melville, the project includes a faux-tourist website, letters, advertisements, interviews, drawings, complaint forms, doctored photos, commercials and mail catalogs stamped with the company’s oblong seal. It’s a thought experiment and travelogue through a real, imagined, lost and found East LA.

On a hot Saturday in late June, Foster invited a dozen or so friends to Romo-Santillano’s house for dinner, poetry readings and a short PowerPoint presentation. We sat around a large dining table and watched images projected onto an ersatz screen, a white sheet tickled by the ceiling fan. The guests were unwittingly impaneled as the official board of directors of the ELADTL, and so, following our hosts’ lead, we slipped in and out of character, chuckling at old-timey images of zeppelins, earnings projections and bar charts depicting “growth in daily ridership.”

In this “real history of a fake transportation company,” we glimpsed actual snippets of a bygone city: a mural effaced, incompletely, by white paint; the 1930s tombstone of an African American stunt pilot. The older artist-activists nodded in recognition at the slides. “Oh, there’s Willie!” or “Hey, didn’t a bank used to be there?”

Toward the end of the night, we watched an earlier product of the ELADTL: a silent, rickety video from 2011 entitled “Pollos Rostizados.” In it, Foster and Romo-Santillano walk along a freeway overpass, chatting about chicken, hot dogs, pickled eggs, old murals, a long-gone gas station and our aerial destiny, the velocity of their mouths mismatched to yellow subtitles. Airships, Foster tells us, are the future of Interstate 10. Soon enough, like the streets and sidewalks that came before, these “fourteen lanes of blackouts, migraines, auditory hallucinations… revolutionary fervor, the ghosts of people buried underneath the asphalt” will fade into the history of East LA.

E. Tammy Kim is a Features Staff Writer at Al Jazeera America. She was previously a lawyer for low-wage workers and an adjunct professor. Write her with tips or comments at tammy.kim@aljazeera.net

Recent Comments